Ann: Some time ago, I got interested in why European languages so often use the same word for “story” and “history.” Every English speaker knows that having one word for two such different things — fiction and truth, respectively — is anathema. But my thinking didn’t go much farther than that, it rarely does. So I found a couple of actual, practicing PhD historians, Audra Wolfe and Alex Wellerstein (bio’s below), and asked them: what’s story, what’s history, are they the same, and if not what’s the relation between them?

Ann: Some time ago, I got interested in why European languages so often use the same word for “story” and “history.” Every English speaker knows that having one word for two such different things — fiction and truth, respectively — is anathema. But my thinking didn’t go much farther than that, it rarely does. So I found a couple of actual, practicing PhD historians, Audra Wolfe and Alex Wellerstein (bio’s below), and asked them: what’s story, what’s history, are they the same, and if not what’s the relation between them?

Audra: Of course histories are stories. History is the study of change over time, which means that it’s an inherently narrative enterprise, with a beginning, a middle, and an end. To be sure, it’s possible to write a history of a given moment in time, a more static account that tries to capture a particular Zeitgeist. But even then, the author has made certain decisions about how that moment of time is defined. Something happened beforehand, to start the era under question, and something happened at the end, to close it.

Ann: Boy, does that sound exactly how I see my own stories: I’m taking the real world and assigning beginnings, middles, and ends. It’s also why I get so worried about using the techniques of fiction in nonfiction.

Audra: But “story” doesn’t necessarily mean fiction! At least colloquially, we describe all sorts of things as “stories”: New Yorker articles, documentaries, and even prizewinning nonfiction books. Eric Schlosser’s Command and Control, for instance, about the oh-so-thin veneer of nuclear safety, is nothing if not a great story. It’s also true.

Alex: I think the term historians usually prefer these days is not “stories” but “narratives,” which is a fancier way to get the same concept across. What is interesting, here, is that narrative structures are very culturally defined, which becomes very obvious if one tries to read direct translations of works from other cultures (the amount of work that has gone into re-purposing the work of the Brothers Grimm, for example, so it flows with more contemporary American expectations about narratives, is pretty obvious if one reads the originals).

Alex: I think the term historians usually prefer these days is not “stories” but “narratives,” which is a fancier way to get the same concept across. What is interesting, here, is that narrative structures are very culturally defined, which becomes very obvious if one tries to read direct translations of works from other cultures (the amount of work that has gone into re-purposing the work of the Brothers Grimm, for example, so it flows with more contemporary American expectations about narratives, is pretty obvious if one reads the originals).

Ann: You know what happens to the wicked queen in the original Snow White? It’s gruesome. What kind of culture thinks this makes a good story? Ok, I’m digressing but it’s clear that “narrative” is different for different people.

Alex: My favorite Grimm non sequitur is the lesser-known “The Twelve Brothers,” which is just one of those stories that requires so much context to make any sense of at all, and ends in an incredibly strange inversion of the Disney style (happily ever after for all involved — except for the step-mother, who gets sentenced to death in a barrel of boiling oil and poisonous snakes).

Narrative requires artistic intervention, it requires choices, it requires a sense of what a good beginning, middle, and end might look like. The historian/philosopher Hayden White has done a lot of interesting work categorizing the kinds of narratives that historians use, and how they affect the kinds of stories being told. It is not, in White’s view, a question of whether there is a correspondence between the historical past (i.e. “the facts”) and the narrative, it is a question of whether the narrative is compelling or not.

Ann: By God, that sounds like heresy. You judge a history by how compelling the narrative is?

Alex: By “compelling,” here, we don’t mean “does it read well” (though that is always nice), we mean, “does it give a structure to the past that seems true?” Which is not the same thing, exactly, as corresponding with the facts — in part because what counts as a “fact” is constrained by the narrative as well. We might have a document in the archive that says something, but a narrative which contextualizes that document is also needed, to make sense of its content. This starts to sound slippery and postmodern, but it is really quite basic and concrete: how do I know a given document is telling the truth? Well, I use other documents, and other instincts and judgments, to make sense of how this document fits into the greater whole, what it actually means. The distinction between the facts and the narrative is a false one — they are inseparable. The stories and the stuff of the stories cannot be separated meaningfully.

Another way to think about this is, if someone tells you a story about their day, how do you know it is true? If the story was, “I went to the store and then I went home,” you probably would find that compelling, unless you had some sort of other narrative evidence that it would contradict (e.g., you had already confirmed they did not go home). If the story was, “I went to the Moon today,” you’d probably not believe it — the narrative would not make any sense, because one does not go to the Moon very easily. Could they, in fact, convince you that they did go to the Moon? Possibly: they would have to elaborate the narrative considerably, to make it seem more plausible that they did rather than they didn’t. (A “hard” and unlikely version of this would involve them explaining that they had in fact been involved in a covert space program, and showing you lots of compelling evidence. An “easy” version of this would be showing that “The Moon” is a new coffee shop in town.) The proper arraying up of evidence, with narrative devices, in stories about the past — this is how we make meaning. Some narratives are more compelling, more plausible, than others. The less likely narratives require much more in terms of supplementary evidence to make them seem more plausible.

Ann: So you’re both saying that history and story, or narrative, don’t have a clear, bright line between them, and I sort of thought they did. And that what I think of as historical facts mean nothing outside of their narratives. And that the best narratives are those with corroborative evidence. That’s a little fuzzier than I thought history was but it makes solid sense.

Audra: Wait, Ann, it gets worse. Historians not only have to decide how they’re going to tell a story, they have to decide what kinds of evidence they want to make use of in the first place. In some fields of history — for instance, classics, or certain areas of medieval studies — it’s possible for all of the scholars working on a given problem to examine the same documents. But Alex and I both work on science and its relationship to the government in the mid- and late twentieth century, a period flooded with documents. We never suffer from a dearth of information. Cold War administrators documented everything and filed it in triplicate. It’s usually not physically possible for a historian of the twentieth century to view “all” of the open (that is, unclassified) archival documents that she might need to write a truly documentary history of a given topic, and that sets aside the problem of what she doesn’t even know is missing (classified information). So, you pick and choose, and, at a certain point, when the documents no longer yield novel information, you stop.

Audra: Wait, Ann, it gets worse. Historians not only have to decide how they’re going to tell a story, they have to decide what kinds of evidence they want to make use of in the first place. In some fields of history — for instance, classics, or certain areas of medieval studies — it’s possible for all of the scholars working on a given problem to examine the same documents. But Alex and I both work on science and its relationship to the government in the mid- and late twentieth century, a period flooded with documents. We never suffer from a dearth of information. Cold War administrators documented everything and filed it in triplicate. It’s usually not physically possible for a historian of the twentieth century to view “all” of the open (that is, unclassified) archival documents that she might need to write a truly documentary history of a given topic, and that sets aside the problem of what she doesn’t even know is missing (classified information). So, you pick and choose, and, at a certain point, when the documents no longer yield novel information, you stop.

A historian has made certain choices even before she enters the archive, in deciding whose papers are worth examining, what correspondence to read, what terms to search in the finding aid. Even deciding to conduct archival research is a kind of choice that privileges the role of institutional and administrative actors over, say, popular culture or mass opinion or demographics or spatial information. And because historians base their accounts on evidence, these choices shape the stories they tell in fundamental ways.

Ann: So I have to add to this fuzzy-history a further fuzziness that comes from what corroborative evidence is available and of that, what historians decide to use. Which of course depends on what narratives they choose. But how do historians choose a narrative? How do they know when the decisions they make about the beginning, middle, and end are — what? true? accurate representations of what really happened? plausible?

Alex: There are probably an unlimited number of ways that a clever writer could tell the same story, given the same essential elements. History is no different, except some of the elements are more “fixed” than a fiction writer’s stories. (Even in fiction, many things are fixed, assuming the fiction is set in roughly the same universe that the rest of us live in; bad fiction becomes implausible.)

Even the basic structure of the story/narrative is an artistic choice. Is the story I’m telling going to be a romantic or heroic one, where the protagonist wins out against the world? Or will it be something more tragic, where the world wins out against the protagonists? Or something in between, as in satires or comedies? These are all different modes for plotting a story out, and when you lay them out like this, one immediately has ideas about how they might apply to one type of historical story versus another. Nuclear history is often told in one of three different narrative veins — the “official story” is usually romantic (where the scientists, or the government, is a hero), the activist story is usually tragic (good people being poisoned, or persecuted), and the Stanley Kubrick version is essentially satiric (the whole world is crazy). Like all writers, historians who are in control of their craft ought to make these kinds of choices purposefully.

Ann: And if you’re interested in Alex’s stories, and you should be because they are, as Hayden White would say — and I can NOT believe I’m about to quote Hayden White — “compelling.” Here’s Romance; here’s Tragedy; here’s Satire.

Alex: As for how we tell these stories — there is no way out of narrative tropes. You don’t get to say, “I’m above all of this.” What you can do is be self-aware, and be in control of the narrative, and do it purposefully. You do try to tell narratives that seem to best represent the past as it can be understood. You hold yourself to high intellectual standards. That doesn’t mean your use of stories, evidence, and judgment will align perfectly with the truth. But history is not a science in any form and should not be mistaken for one. It is a form of writing about the past that relies upon empirical evidence, among other forms of reasoning, as a guide. Some historical narratives are more compelling than others. And there is nothing more constant in history than the fact that later historians will find earlier histories inadequate.

____________

Alex Wellerstein is an historian of science at the Stevens Institute of Technology who writes about nuclear weapons and nuclear secrecy, and whose blog Restricted Data is a charming and thorough education in how to tell stories.

Audra Wolfe is a Philadelphia-based writer, editor, and historian, and is the author of Competing with the Soviets: Science, Technology, and the State in Cold War America. She’s currently writing a history of science diplomacy. Incidentally, she wrote a lovely riposte to — “take-down of” would be a less-polite word — Neil deGrasse Tyson’s Cosmos.

___________

The font colors above were, I think, Alex’s idea — we set up this conversation originally in a Google Doc and he assigned us red, green, and blue. Just so you know.

___________

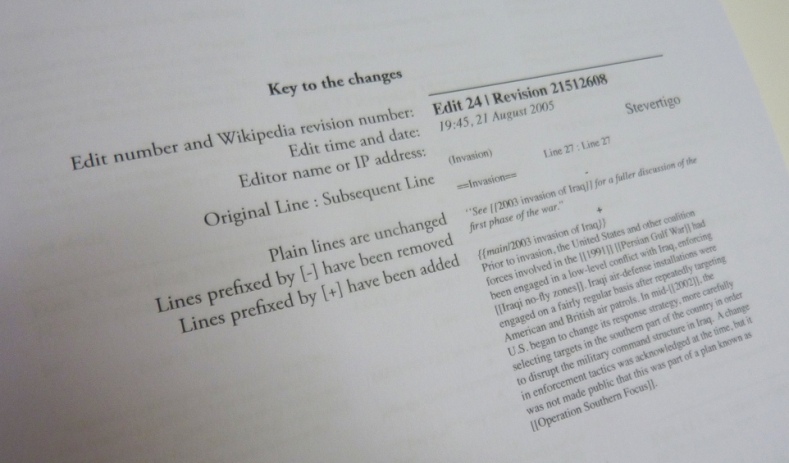

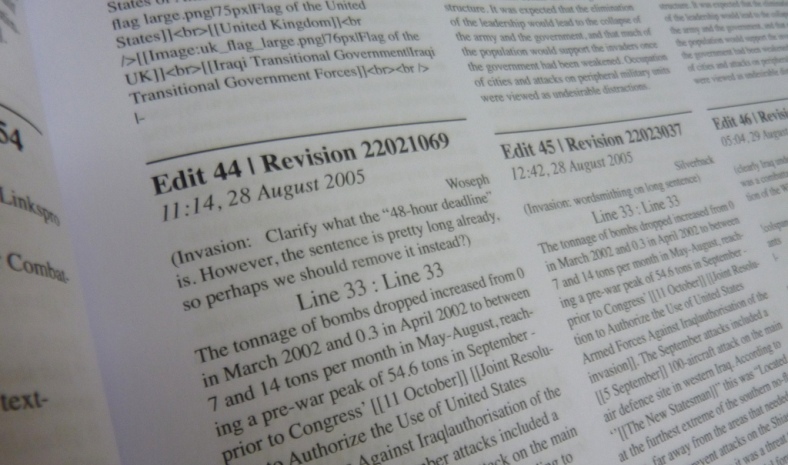

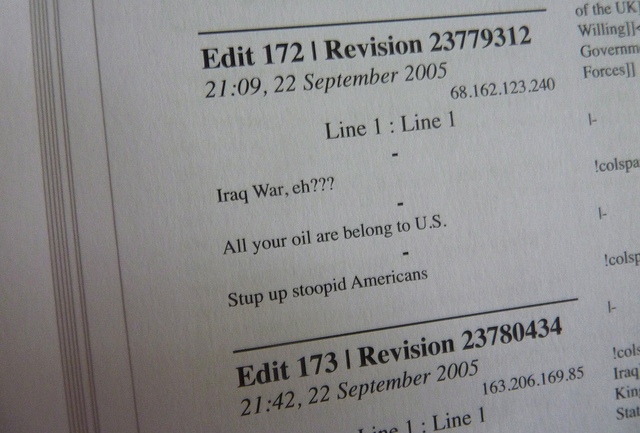

Photos are from a remarkable book that’s a compilation of Wikipedia edits, via Flickr. This is what the author, James Bridle, says, and it’s not at all irrelevant: This particular book—or rather, set of books—is every edit made to a single Wikipedia article, The Iraq War, during the five years between the article’s inception in December 2004 and November 2009, a total of 12,000 changes and almost 7,000 pages.

It amounts to twelve volumes: the size of a single old-style encyclopaedia. It contains arguments over numbers, differences of opinion on relevance and political standpoints, and frequent moments when someone erases the whole thing and just writes “Saddam Hussein was a dickhead”.

This is historiography. This is what culture actually looks like: a process of argument, of dissenting and accreting opinion, of gradual and not always correct codification.

And for the first time in history, we’re building a system that, perhaps only for a brief time but certainly for the moment, is capable of recording every single one of those infinitely valuable pieces of information. Everything should have a history button.